Although the exact etymology is a bit murky, the word vandalism is indelibly associated with an East Germanic tribe best known for the sacking of Rome in 455 AD.

The unflattering connotation is also a matter of debate among scholars. The Vandals, not unlike the Celts and other nomadic people in Europe, failed to chronicle most of their records. As a result, Roman scribes typically labeled them “barbarians,” as did later ecclesiastical accounts, providing yet another example of how the winning side often writes history.

Recent archeological discoveries have challenged previously held notions about the Vandals being merely uncivilized brutes. That said, let’s take a look at this much-maligned group who may or may not have torched a few chariots and tossed eggs at Roman soldiers.

What’s Your Name?

The ancient author Pliny the Elder provides the earliest mention of the Vandals in his tome, Naturalis Historia. He used the broad term Vandilii in 77 AD to describe one of the major groupings of Germanic tribes found on the outskirts of the Roman Empire.

As a word of caution, labels such as ‘Germanic’ can be misleading as they could imply a national identity that didn’t exist. Moreover, tribes from the region were just as likely to attack each other as they were the Romans. Even the word ‘tribe’ can be problematic as well because these groups comprised of various constituents within a confederation sharing the same cultural practices and language.

The name may also stem from the German word vand, which means “to wander.” Lastly, a connection is possible to those living in Vendel, a province in Uppland, Sweden, where the Vandals most likely originated.

On The Go

Around 130 BC, the Vandals’ embarked on a long migration that started in the frigid tundra of Scandinavia and ended up in sun-baked North Africa. The meandering route included a stopover in Silesia (modern-day Poland), where they possibly contributed to the Przeworsk culture.

Along the journey, the tribe divided into separate factions, the Silingi and the Hasdingi, before continuing southward. The nomads began arriving on the outer borders of the Roman Empire during the 2nd century AD and participated in several clashes along the Danube, including the Marcomannic Wars.

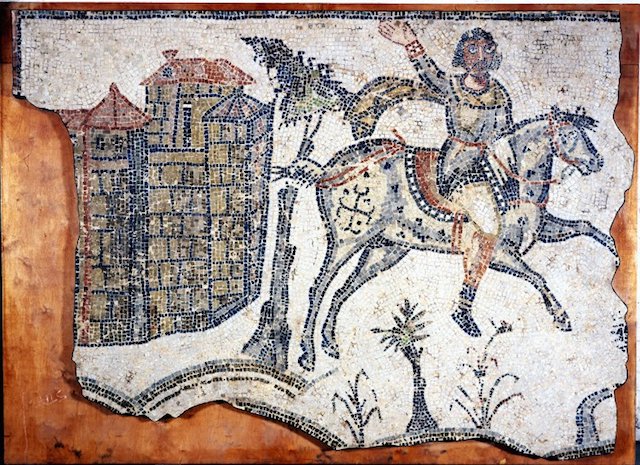

They gradually became more adept in the art of warfare while invading new lands. The Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius would later grant them the right to settle in the territory of Dacia (modern-day Romania) in exchange for their martial skills as mercenaries —especially as horsemen. Constantine the Great later employed a similar strategy in other long-forgotten Roman provinces such as Pannoia, Noricum, and Raetia.

The late fourth century saw the Huns accelerate their rampage across Central Europe, pushing other “barbarian” groups further south and west towards Rome. The Vandals fought their way across the Rhine into Gaul before moving into the Iberian peninsula. Finally, under their leadership of their dynamic and vastly underrated King Gaiseric (more on that later), they settled in North Africa.

Friend or Foe

The story of the Vandals reveals an eventful rise and fall before rather abruptly fading into obscurity. In a span covering roughly six centuries, they found themselves as both the conquered and the conqueror, making alliances and sworn enemies that involved more subplot twists than The Godfather trilogy.

The Vandals and Visigoths clashed frequently despite hailing from roughly the same area as the Visigoths (Goths = of German culture) and following similar migratory paths. But that particular beef is only a small part of the picture. Here’s a handy cheat sheet of their many friends and foes…

Alans: friend

Alemanii: friend

Burgundians: friend

Byzantines: foe

Huns: foe

Maniots: foe

Marcomanni: friend

Moors: foe

Romans: friend and foe

Suebi: foe

Visigoths (western frontier Goths): foe

We Say Nay, You Say Heresy

As Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire in the early fourth century, the Vandals practiced a nontrinitarian Christological doctrine called Arianism. The movement, based on the teachings of a priest from Alexandria named Arius, would be later branded as heresy by the Church in Rome.

The controversy began when Arius challenged the notion of the Holy Trinity. He contended that if Jesus, as the son of God, was created by the Father, then he was, therefore, neither coeternal nor consubstantial. In other words, the boy from Nazareth didn’t hold as much weight as the man upstairs.

The debate presented a significant crisis for the early Church, prompting Constantine the Great to intervene in 325 AD by summoning the First Council of Nicaea. Constantine, who later became the first Roman Emperor to convert to Christianity (well, sorta), presided over the landmark discussions and the first ecumenical council of the Christian Church. The gathering of over 200 bishops deemed Arianism heretical and enshrined the divinity of Christ in a statement of faith known as the Nicene Creed.

Regardless, the Vandals and other new arrivals to the Roman Empire held steadfast in their beliefs — a position that would perpetuate their legacy as unruly heathens. It’s worth noting that Constantine boiled his wife to death and killed his son but still emerged as the ‘great one’ in the eyes of the Church. Go figure.

Arianism, like many cults, would gradually fizzle out over time. However, rejection of the Trinity by Christian denominations is still prevalent today, most notably by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

The King’s Kingdom

At its peak, the Vandal realm encompassed a long stretch of North Africa covering what is now modern-day Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya. They made the historic city of Carthage its capital, establishing a strong strategic position along the Mediterranean coast that also allowed them to take control of Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, Mallorca, Malta, and Ibiza.

The ascension of King Gaiseric (also spelled Genseric) to the throne in 428 AD marked a significant turning point in the Vandals’ rise to prominence. The nomadic tribe had been living in the Roman province of Hispania Baetica, where several bloody battles against the Visigoths had taken its toll. Gaiseric chose to pack up and move again — but this time to a region mired in chaos and dissent — and therefore vulnerable to invasion.

The crafty leader took his army across the Strait of Gibraltar and set his sights on Roman-controlled North Africa. Beginning in 430, he won a series of battles in the provinces of Numidia and Mauretania against forces led by Bonifacius, a Roman general and governor of the Diocese of Africa. The fighting included laying siege to the ancient walled city of Hippo Regius that resulted in the death of its renowned Christian bishop, Saint Augustine.

As the Gaiseric’s empire grew, he also built a powerful fleet of ships to wreak havoc with seaborne raids along the coastline. The Romans, now fearful of the upstarts’ new power, hoped to appease them by negotiating a succession of treaties and accepting Genseric as the head of Pro-consular Africa. After centuries on the move, the Germanic tribe finally had a secure homeland.

Sackimus Maximus

The much-ballyhooed sacking of Rome would primarily come to define the Vandals place in history. However, the treachery of a few Roman emperors deserves much of the blame. In the mid 440s, the Emperor of the Western Roman Empire, Valentinian III, attempted to strengthen Rome’s Vandalic alliance by betrothing his youngest daughter, Eudocia, to King Gaiseric’s son, Huneric. However, any hope of a mutually beneficial union and happy marriage soon went up in smoke.

A power-hungry and wealthy senator named Petronius Maximus plotted a coup against Valentinian. Adding to the drama, the sitting Emperor had previously raped his wife. The vengeful Maximus waited for the stars to align and had his venal rival whacked, causing all Hell to break loose. The new ruler then forced Valentinian’s widow, the Empress Licinia Eudoxia, to marry him and decreed that his son, Palladius, would now marry Eudocia. Meanwhile, Gaiseric sensed an opportunity to exploit the imperial discord. He declared all treaties with “The Eternal City” as null and void, and prepared to march on Rome.

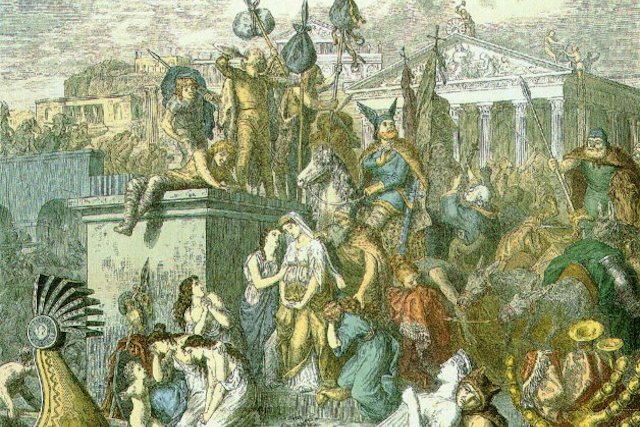

Facing imminent ruin, the Romans sent Pope Leo I to plead for mercy. The papacy still viewed the Vandals as heretics, but the pragmatic Gaiseric agreed not to destroy the city or slaughter its people in exchange for unlimited plunder. And for the next fortnight, plunder they did. The invaders confiscated anything of value — even stripping gold leaf from the roof of the Capitoline Temple. Exhausted from their wanton binge, the victors sailed home to Carthage loaded with loot, taking with them the former Empress and her daughters.

As for the fate of Petronius Maximus, an angry Roman mob stoned him to death outside the city walls when he tried to flee. His doomed reign had lasted a mere six weeks.

The Robber Got Robbed

After fleecing Rome, Gaiseric’s legacy would be later ransacked in one of the greatest historical ironies ever. The man who built a mighty empire, reigned 50 years and NEVER lost to the Romans became a mere walking shadow on history’s global stage. Meanwhile, his contemporary, Attila the Hun, continues to bask in eternal infamy.

Nearly every list of the top military leaders of all time includes the ruthless Hun. Dubbed as “Flagellum Dei” (“Scourge of God”), legend has it that his wrath not only spread fear on two continents, but the grass never grew on the spot where his horse had trod. Uh huh. Although most tyrants are guilty of touting alternate facts, the diminutive despot routinely comes up short next to the Genseric.

First of all, the Hunnic Empire, although much bigger than the Vandals, wasn’t exactly high end beachfront real estate. Most of Attila’s villas stood in large swaths of harsh, uninhabitable terrain, including all of Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan! Meanwhile, Gaiseric held court over the choicest spots in the Mediterranean, where centuries later, crowds still flock to the cool sea breeze and inviting warm sand.

Furthermore, the Romans and Visigoth combined to defeat the Huns at the Battle of Catalaunian Plains in 451 AD. Attila died two years later at the age of 43 after choking to death on his blood while in a drunken stupor — and on his wedding night no less. For those keeping score, Gaiseric lived to the ripe old age of 88.

Nothing Lasts Forever

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dn8Frkrlts8

Between 460 and 475 AD, Roman forces attempted to reclaim their influence in North Africa and unseat Gaiseric from power. They failed. Miserably. The Vandal King’s shrewd military tactics — not to mention his cunning, uniqueness, nerve, and talent — allowed him to thwart all comers. But his death in 477 of natural causes (rare in these stabby times) would lead to a rapid decline from which the Vandals would not recover.

Gaiseric’s oldest son, Huneric, inherited the throne from his father but never managed to fill the old man’s shoes. The Kingdom would suffer from a string of internal conflicts that hastened its demise. Eventually, the Eastern Roman emperor, Justinian I, made expelling the Vandals his top priority. In 533, Carthage fell and forced Gelimer, the last Vandal King, into exile.

On a positive note, the ’80s California punk band, The Vandals, took inspiration from the ancient group and is still going strong today.