The word “gospel” literally means good word. From the 1st century onward, professed Christians have tried preaching their message in the language of the people whom they encounter. Because many languages in the past existed merely as spoken languages, without any written literature, it was difficult to discuss the doctrines of the scriptures with these illiterate tribes. For the past 2,000 years, missionaries have given people around the globe the gift of literacy by devising alphabets, syllabaries, and primers in order to spread their religious message.

10. Ufilas and Gothic

Historians know that Ufilas was a preacher to the Goths in the 4th century, but we have little personal information about him. Researchers believe that he was a descendent of Cappadocians captured by Goths and resettled in their territory. The limits of the land of the Goths are still unknown as they were largely a nomadic people. However, since Ufilas provided the tribe an alphabet, we can trace current Germanic languages back to their Gothic ancestor-tongue.

Prior to receiving this alphabet, the Goths, like many Northern European peoples, used runic writing. Unfortunately, runic writing is ill suited for the propagation of complex ideas. The Goths thus likely had difficulty grasping many of the doctrines taught by missionaries.

After the church consecrated Ufilas as bishop of the Goths, he wanted to reach both their hearts and minds. Using his knowledge of Greek and Latin, he devised for them an alphabet for their language. Later, he translated most of the Bible into Gothic, although currently we only have the gospel accounts and a few other books of the Bible. This Bible was Gothic’s first work of literature. Interestingly, he served as an Arian (non-Trinitarian) bishop during this age of fierce theological debate about Christ’s nature, and this differing influence contributed to the Gothic (Germanic) peoples defining themselves apart from the Latin and Greek cultures.

9. Stephen of Perm and Old Permic

During the 14th century, when the Russian Orthodox Church sent Stephen to preach to the Komi people, he should’ve had it easy. Although Stephen was ethnically Russian, he had been born among the Komi, who lived in the northeast of European Russia. However, bad relations existed between the Komi and the Russian governments. Culturally distinct from ethnic Russians, the Komi had to send tribute to the capitals Novgorod and Moscow. They thus didn’t take kindly to Russian people or their customs.

Stephen believed that in order for the Komi people to accept Orthodox Christianity without resentment, they needed to retain aspects of their culture. He decided to use the names of the local deities in order to introduce them to characters such as Almighty God, Jesus Christ, and Satan. Furthermore, instead of forcing the people to use the Cyrillic alphabet of the Russians, he gave them an alphabet adapted from their mother tongue’s use of Tamga signs, but still modeled on Greek and Cyrillic characters. Later, Stephen founded schools to teach the language and the new alphabet. As a result, Old Permic lasted another three hundred years until Russian replaced it as the primary language of the Komi people.

8. Uyaquq and Yugtun

Most people familiar with inventors of writing systems have heard of Sequoyah, an illiterate Cherokee who invented an alphabet for his tribe. Uyaquq, a late 19th century Alaskan Eskimo, wanted to accomplish the same thing as Sequoyah, as he wanted to spread the gospel more easily among his tribe.

Born into a family of shamans, Uyaquq converted to Christianity after his father had converted. Although his father joined the Orthodox Church, he became a member of the Alaskan Monravian Church, and expressing his dedication to his new faith, he later became a missionary. Impressed that English-speaking Monravians could quote scriptures using exactly the same words each time, he found out that the reason why was that they were reading texts. He however failed to learn to read or write English properly.

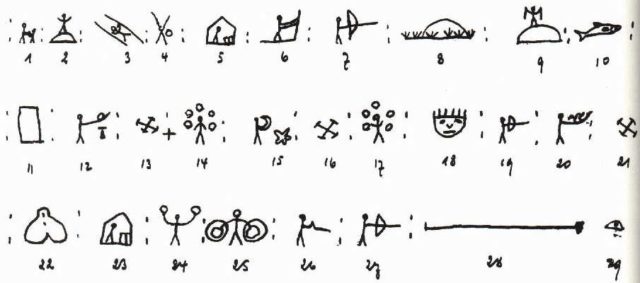

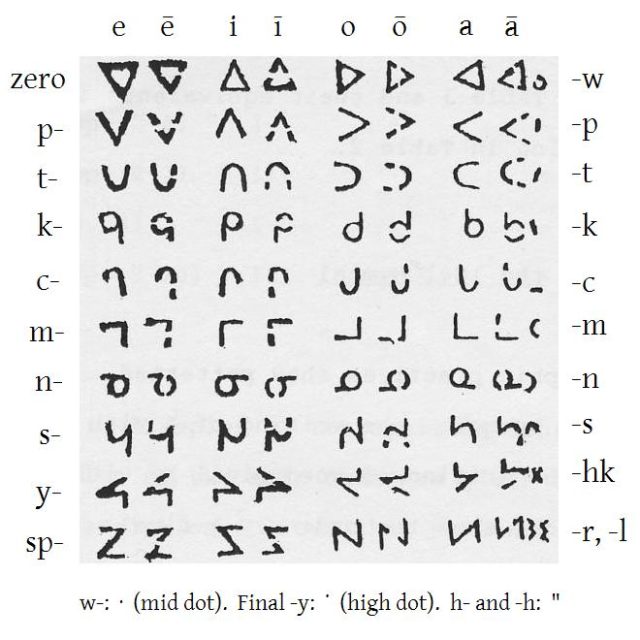

After having a fantastic dream, he originally created a pictograph system, which is where images represented words. Uyaquq was still not satisfied, and after coming in contact with missionary John Hinz, who encouraged him his linguistic work, he developed his system into an actual syllabary. Later, another tribesman further developed the alphabet by creating different symbols, but he still used Uyaquq’s work as the base from which he worked.

7. James Evans and Objiwe and Cree

Prior to Uyaquq, there was another man impressed with the achievements of the self-taught Sequoyah. This man—James Evans— came from an entirely different cultural background; he was an educated English-born Methodist, assigned to the Manitoba province of Canada, and he had the responsibility of teaching Native students, but not all of his students could read and write English. He however knew multiple native languages, and he was particularly fluent in Objiwe. He started to develop a complete writing script for the tribe, but he stopped when the students became confused as both English and his proposed Objiwe alphabet had the same script. He thus decided to give them a more basic shorthand-based syllabary.

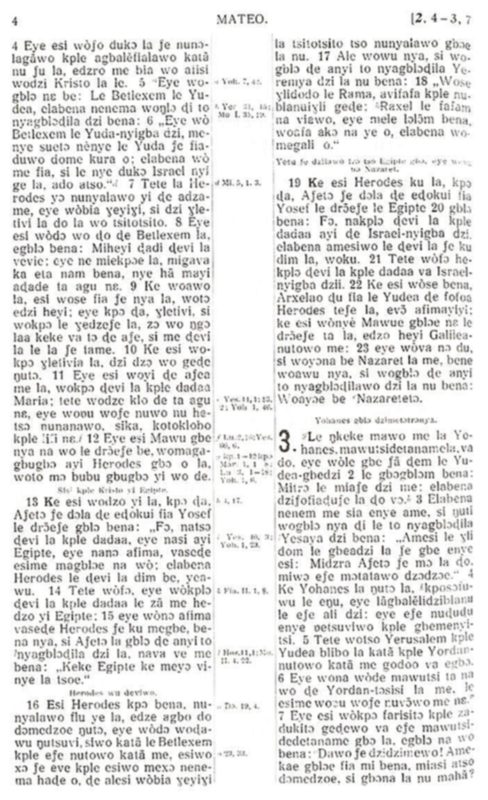

Learning from his previous mistakes in developing an alphabet, twenty years later, Evans tried his hand in giving the Cree people a writing system. Because he was still having difficulty adapting a native language to the Latin alphabet, Evans decided to use the Objiwe syllbary that he had invented earlier to help with his work in Cree. It was a success, and his first published work in Cree was a hymn, “Jesus My All to Heaven is Gone.” His system was soon popular enough that nearly all the Cree community became literate.

6. Diedrich Hermann Westermann and Ewe

Very few Westerners have likely heard of language Ewe. Even fewer probably know how to pronounce the word (Just a hint, it’s different from the word for a female sheep). It’s a language in Sub-Saharan Africa, and in Ghana, where the official language is English, and in Togo, where the official language is French. It is considered to be the national language or the language of the common people.

Westermann was man a devoted to the African people and to the study of African linguistics. Sent in 1901 to the German colony Togo as a missionary, he developed a knack for learning multiple African languages, and he enjoyed discovering how they related linguistically. For instance, he was the first person to group Bantu languages together and to see how they fit in the greater context of West African linguistics. His primary work though was with Ewe, and he was able to compile multiple grammars and a Ewe dictionary. Today, this dictionary (revised later in 1954) is still important in the field of African linguistics.

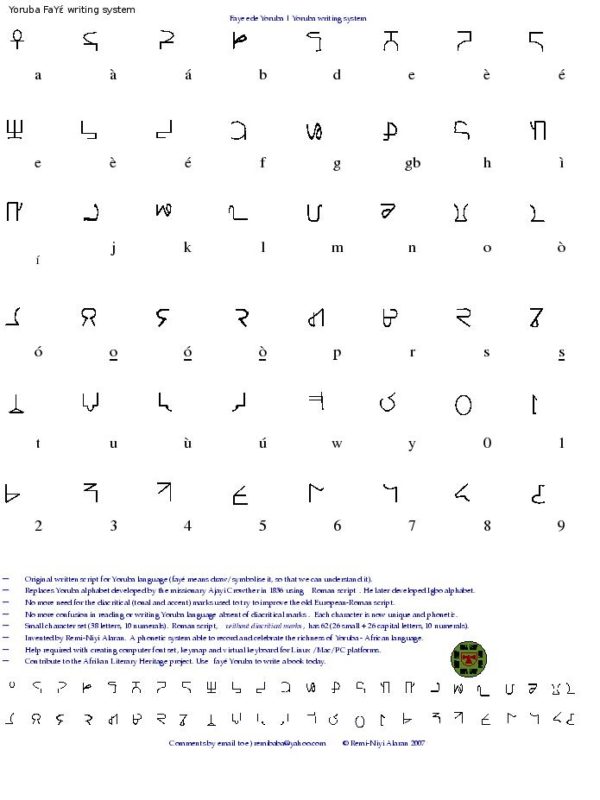

5. Samuel Ajayi Crowther and Yoruba

Samuel Crowther also served in Africa, and he led an even more eventful life than Westermann did. Muslim slave traders first captured him when he was a thirteen-year old Yoruba boy, and during a significant period, slave traders bought and sold him five more times. While being held on a slave ship one day, the British initiated an attack against the slave traders and liberated him. Afterwards, he converted to Anglicanism under the influence of a missionary assigned to Africa—John Raban.

Later in England, the Anglican Church ordained him as the first African bishop. Since he was an African native, they assigned him back to the continent, where he began his endeavors in ministering to his fellow Yoruba. Earlier, Raban had written a few books about the Yoruba language, but there was still no Yoruba primer or dictionary available. Crowther now knew what he must do. Although there had been a previous translation of the Bible into Yoruba, many native speakers felt it was lacking. Because Yoruba was comprised of many dialects, it was often hard for the speakers of the many dialects to understand each other. Crowther thus decided to standardize those dialects into a single Yoruba language. Having accomplished that, he then served as the chief contributor to a new translation of the Bible. His efforts in uniting the Yoruba language led to the uniting of fragmented tribes into a single Yoruba people.

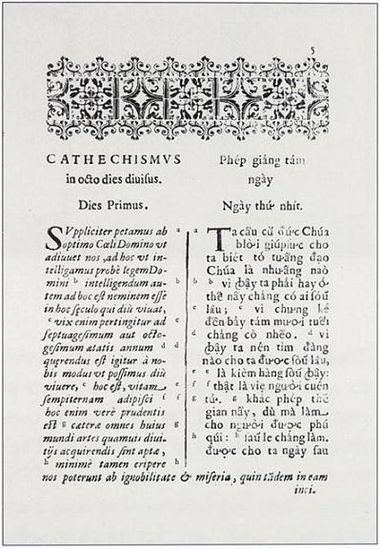

4. Alexandre de Rhodes and Quoc Ngu

Vietnamese wasn’t always written with a Latinized alphabet. Prior to the 17th century, the Vietnamese used Chu-nom, which is a Chinese-based script. The language still had many Chinese loanwords long after Vietnam developed its own national literature and made efforts to distinguish themselves from the more populous nation to the north. If a person knows the history of Chinese-Vietnamese relations, he or she understands that the situation has rarely been convivial. Vietnam was thus ready for a change in their written language.

In the early 17th century, Jesuit missionaries began arriving in Vietnam. Before Alexandre de Rhodes arrived, there had been early efforts in compiling a Portuguese-Vietnamese dictionary. Rhodes however set the stage for the Vietnamese eventually adopting a new alphabet. Rhodes was not even Portuguese, but French, and he used those previous Portuguese translation efforts to assist him in creating a Vietnamese dictionary. He called the new Latin-based script Quoc Ngu. Later efforts by missionaries in supporting the Quoc Ngu script helped convert many of the population to Catholicism, and by the 20th century, Chu-nom had all but fallen into disuse.

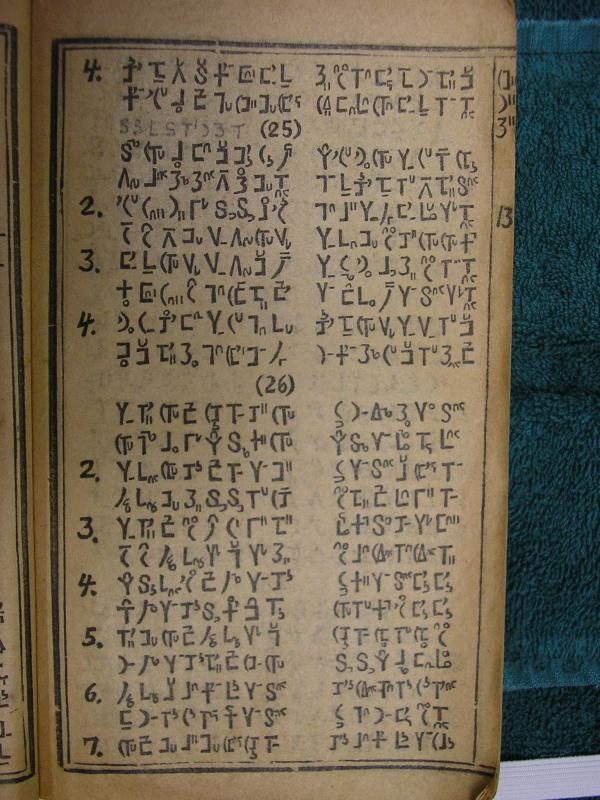

3. Sam Pollard and Miao

China was a large field for missionaries during the 19th century. Not only is the landscape vast, but the country, particularly away from the population centers of the east, is composed of numerous tribes and languages. One of these minority groups is the Miao or A-Hmao, who live in the Guizhou and Yunnan provinces to the south.

Before Pollard arrived in 1904, the A-Hmao used Chinese characters for their language—a language that they rarely wrote down. When Pollard learned that the Han Chinese viewed the Miao people as barbarians, and saw their mistreatment firsthand, he sympathized with the ethnic group. He realized that Chinese Bibles and hymnbooks would not help the A-Hmao. He thus developed a Latinized set of symbols that would effectively represent the southeastern origin of the language.

It proved popular with the people; when the communists later wanted to replace Miao with a language system based on Mandarin, the tribe resisted. Interestingly, the Miao writing system, despite its need for revisions over the years, is so embedded in their culture that some A-Hmao believe that their tribe invented the writing script, which then had become lost for years, but they then had “rediscovered” it with the help of Pollard.

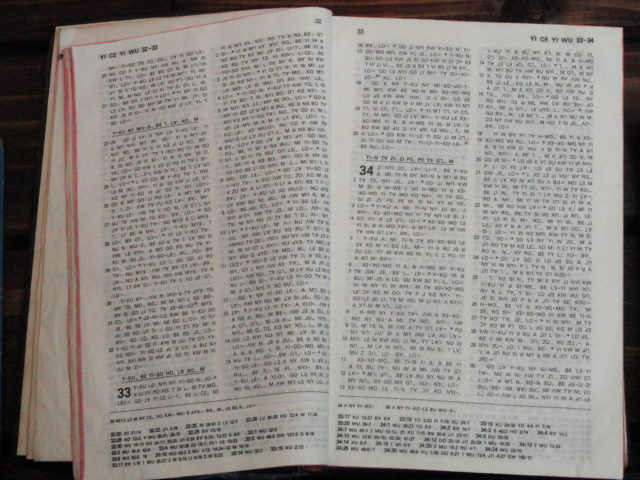

2. James O. Fraser and Old Lisu/Fraser

James O. Fraser was another Englishman in the Yunnan province, but he served in it a few years later. He directed his preaching toward the Lisu people—another minority situated along the Burma-Thai border. During the initial years of missionary work, a fellow preacher, but of Karen descent, invented the basic form of the Old Lisu alphabet. Although appreciating the work of his colleague, Fraser believed that there could be improvements in the system.

Fraser organized the system so that the writing went from left to right in horizontal lines. Like some other Southeastern Asian languages, Lisu is tonal-based, so Fraser used punctuation indicate differing tones. The alphabet itself consists of uppercase Latin characters. In order to differentiate sounds, some of these characters are rotated 90 or 180 degrees.

Despite his depression and his uncertainty about his ministry near the end of his life, his efforts were largely successful as there are currently about 300,000 professed Lisu Christians in China, with unaccounted others in Thailand and Myanmar. Even the Chinese government eventually recognized the writing system’s importance as they confirmed that it was the Lisu people’s official script in 1992.

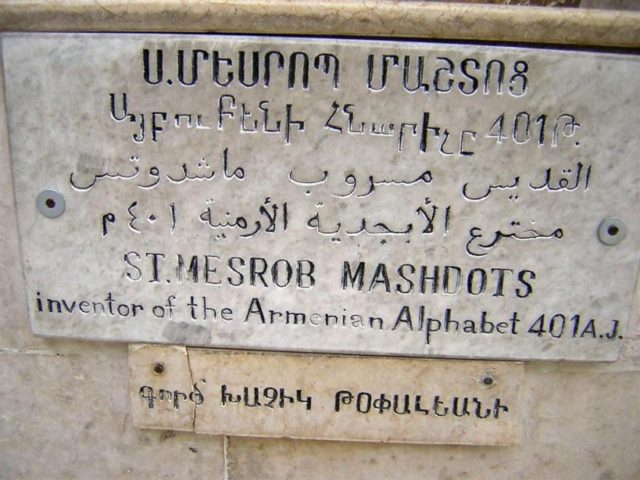

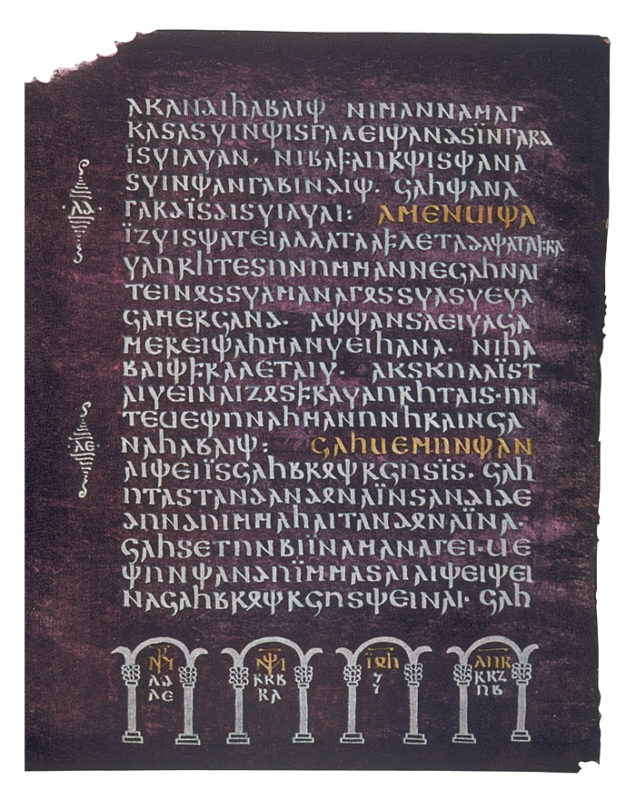

1. Mesrop Mashtots and Armenian and Georgian

The history of Armenia is fascinating. In 301 A.D., the small country became the first nation to declare itself Christian. Situated between the Eastern Roman Empire and Persia, it was constantly facing invasion by massive armies at the end of the 4th century. It was during this chaotic climate that a bishop decided that Armenia needed a written alphabet.

With all the external strife occurring, why did Mesrop feel the need for an alphabet at the time? Because the masses could not understand Greek or Syriac, the languages of the Armenian Church at the time, many of the people were falling away from the faith. They needed a writing system in which the average person could read the scriptures. Mesrop also believed that Armenia’s culture was about to be swallowed by foreign influences. Many of the nobles were pro-Persian, while the Syriac-speaking clergy wanted to push the traditions of the Antioch Church on the Armenians.

Having received support for his initiative from the head of Armenian Church and given a mysterious set of letters composed in a defunct Armenian script from Bishop Daniel, Mesrop set out on his task. Successful in creating a new alphabet, he went on a missionary tour of the Armenian countryside, and brought back many into the church. Furthermore, although there is less information about the creation of the Georgian and Gargarean (dead North Caucasian) alphabets, historians credit him for inventing these alphabets due to the similarities between them and Armenian.

3 Comments

No Cyril and Methodius?

other alphabets are really weired!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

hey mesrop mashtots never invented georgian alphabet. No one knows who really did it. every good historian who ever learned georgian history or historic sources about mesrop knows that he never invented Georgian alphabet. greatest proof of it is that Mesrop did not know georgian language. how you can invent alphabet for language which you don’t know? in georgian language every sound has it’s symbol. georgian language is not indo-european like armenian. we have very unique sounds which are not in european languages. And he did not spread the Gospel. at least he did not spread the gospel in georgia for sure. georgia in time of Mesrop was already christian. yes there are some similarities in look between old georgian alphabets and armenian but both have different order. and have in mind that georgia is eastern orthodox country when armenia is gregorian! in middle ages there was conflict between georgian and armenian churches. many thinks that this story about mesrop inventing georgian alphabet was made up after that conflict because all the sources about that date after church conflict.